Admiral:

Ian Sturrock, Senior Lecturer in Game Design and Games Studies at Teeside University, has written a concise article for The Conversation on the success of Games Workshop as a company. It’s an easy read. This article, and some highlights in the following discussion on DakkaDakka, may be fascinating for anyone curious about such things.

Sharing here in case anyone find it interesting:

The secret of Games Workshop�?Ts success? A little strategy they call total global domination

‘Wait till you see the army coming over the hill.’

In an era defined by online shopping and falling real incomes, the high street can seem like a morass of zombie companies, hauling their carcasses from one sales season to the next until someone puts them out of their misery. One honourable exception is Games Workshop, a company that makes its money by selling zombies instead, alongside wizards, space orcs and all other accessories for the dedicated fantasy gamer.

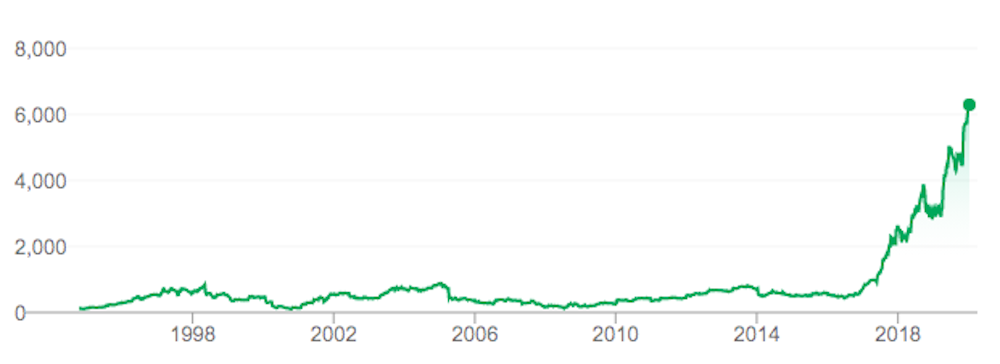

Had you invested £1,000 in the firm�?Ts shares at the end of 2009, you would now be sitting on a pot of more than £25,000. The company is the best performing FTSE250 retailer of the past decade �?" and second best performer overall. So what�?Ts going on in those dungeons? What lessons can this impressive operator teach the rest of the high street?

Founded in London in the mid-1970s by Ian Livingstone and Steve Jackson �?" who would later became famous for co-authoring the Fighting Fantasy choose-your-own-adventure books �?" Games Workshop evolved quickly in its first few years of existence. It went from manufacturing and distributing traditional board games to focusing on fantasy fare, above all Dungeons & Dragons, the cult role-playing game from America that would define the whole genre.

The company soon launched the White Dwarf magazine, which became a bible for fantasy gamers, and moved into manufacturing miniatures for wargaming under its Citadel Miniatures brand. It soon began to build its business around these miniatures and, to a lesser extent, the Warhammer tabletop fantasy game, which launched in 1983. By the mid-1980s, White Dwarf had stopped covering Dungeons & Dragons and other people�?Ts games to solely concentrate on the Games Workshop universe.¨

Let battle commence

This narrow focus has essentially continued up to the present day. It is key to understanding the business. To investors and retail staff alike, the company has long referred to its strategy as �?ototal global domination�?�. It barely acknowledges the existence of competing games or miniatures, perhaps with good reason; it has no real competitors who can match its vertical integration in the marketplace.

Most other wargames manufactures are just cottage industries with no presence on the high street: the next most successful achieves less than 2% of Games Workshop�?Ts £257 million turnover. The company�?Ts stores stock only its own products, though it is more than happy to sell them elsewhere: 47% of sales come from third-party retailers, while a further 19% are online.

Games Workshop�?Ts share price

Staff have regularly described the company as making the �?obest fantasy miniatures�?� in the world. Where most big Western retailers outsource manufacturing to contractors on the other side of the world, the firm makes almost everything at its own factory in Nottingham in the English Midlands, also the place of the company headquarters.

Games Workshop now has 500 stores worldwide �?" a fifth of them major outlets, while the rest are one-vendor operations like the one pictured below. Most of the bigger stores are in the UK, Europe and Australia, and total global domination has no room for passengers: loss-making stores are quickly reorganised to make a profit, or closed. There are also a smattering of stores in North America and Asia, though the company has never achieved critical mass in those markets like it has in the UK.

Our man in Strasbourg.

It is clear from my own research that stores function at least as much as clubhouses devoted to the hobby: collecting, painting and occasionally even gaming with the miniatures. Fans and customers obsess over both these figures and the complex fictional worlds in which the games are set.

Everything is built around two settings �?" one fantasy and one science fiction. You could legitimately accuse them of being derivative of the pop culture over the past half-century or so. But they function as fully realised, complex worlds complete with spin-off novels, comics, card games, computer games, and even a film �?" though Ultramarines: A Warhammer 40,000 Movie was hardly a classic. The logic is to give the dedicated fan so much to consume that there is no need, or indeed very much time, to bother with anything else.

One potential threat to this close relationship with customers in the past was the company�?Ts approach to defending its intellectual property. Its legal department long had a reputation for zero tolerance, attracting heavy criticism, for example, for taking action to prevent an author from selling a book about space marines. My sense is that the company has become much less litigious since Kevin Rountree took over as CEO in 2015.

Treasure chest required

Buying into the Games Workshop hobby is not cheap, it should be said. You can easily pay over £50 for just a dozen plastic figures, for instance, plus another £25 for paints and brushes. This attracts regular gripes from both fans and the press, and is presumably integral to the company�?Ts surging share price and mainly strong financial results.

Yet steep prices are only viable if the product is good enough. The company has regularly rebooted and reinvented its own games and worlds over the years, though arguably they can never be well enough tested to satisfy competitive gamers. The complexity of each game system and the need to bring out new versions to sell more models tends to mean that one strategy becomes too dominant.

The company has also innovated in other ways �?" recently, for example, formulating revolutionary new paints and painting techniques to make it easier for the customers to get great results with their figures.

Steady as she goes.

Can the success story continue? There seems every reason to assume that it can. It might even benefit from the mounting concerns around the carbon emissions from video gaming, and the need to transition to low-carbon computing.

Though Games Workshop certainly makes money from branded video games, being anchored in physical products and stores that offer a communal experience could be a good place to be in years to come. So long as you can save your prized miniature collection from extreme weather events, Warhammer 40,000 and Age of Sigmar will continue to be playable in a post-carbon economy. For a company that has done so well out of dystopian fiction, that would arguably be a fitting turn of events.

Ian Sturrock

Nice article and it is good to see a company bucking the trends today! Two thoughts for a followup article and I think are every bit as important as part of not only why they’ve survived the years, but also grown (esp as much of the rest of the market is faltering)

1) Loans - far as I’m aware GW has never (or exceptionally rarely) used loans to fund their expansion. This might have meant that they expanded slower in their early days, however they’ve also not got a big debt standing over them. Thus every time recessions have hit, whilst things have got tougher, they’ve not had big loans to drain their coffers at unsustainable rates. Indeed you often find that many of the big highstreet names start to falter because they took out massive loans to fund fast expansion, which then come back to bite them when recessions hit and the profit margins contract.

2) I think it can’t be understated how important their attitude and marketing shift was in that huge sales spike that took them to leading the stockmarket for a while. I think its an important lesson and study in the attitude of a company when it trades on the stock market between having an attitude that’s “for the shareholders” and one that’s “for the customers”. Even if in part its only how the company presents and communicates with those two groups.

GW gives a really bold display of this when they gave customers what they’d ask for for years in terms of full rules updates for the major games in short windows (as opposed to their old method of years - even decades sometimes); and also started a far more direct marketing campaign to their customers and engaging with them at a slightly higher level. Heck GW now markets 365 days a year which honestly I’m hard pressed to think of any other company that markets that hard in a direct sense to their customers (as opposed to using billboards/TV ads/etc…).

Also a note on the stores. I’ve seen many retain a store within a region/town; but over the years one other trick GW has used to remain profitable has been to move out of the most central highstreet region and into the slightly cheaper parts. Typically on the fringes of the main highstreet, so they aren’t hidden in a backwater street and still get decent footfall; but where the rent is certainly lower/more affordable.

Overread

Nice article. I work in investments so spend a lot of time on this side of things. The dominance will continue as it truly goes global in the next decade - the trick will be taking experts in a given field and having them translate the GW IP into that media/region (instead of GW trying itself). The netflix series will be an interesting shot for them. However, lots of people video game GW IP and don’t touch the miniatures, the customer conversion on that is relatively slim based on what I’ve been able to gather.

I expect some minor restructure before 2030, with even more definition between making models and marketing out the IP. There are rumours of an in-house blue screen stage and some weta workshop style crafting ability as part of extending their facilities… so more video content… hobby related and also dramatic.

Nothing new here, just my 2 cents on the back on your well written article.

A rival of this magnitude materialising isn’t out of the question, however the popularity is more of a macro-trope, much like Dr Who or Star Wars. There are alternatives to Star Wars… but it’s not really Star Wars.

GW don’t have anything to worry about.

MOTN

A few thoughts on 3D printing:

1) Layers / sanding is a problem for SLA / PLA printers. This doesn’t affect resin printers much at all, these days, the quality of the best consumer grade printers is on-par with standard GW kits. Even the low end ones are printing at about 25 microns. Reminds me of dot-matrix printers, there’s much better solutions out there.

2) Prices for resin printers is coming down. The Anycubic Photon is like $300, I’ve seen the Formlabs 2 selling at $2,200. There are plenty of steps in-between. YTY price drops trend at about 13% on the popular ones, and companies continue to innovate.

3) Don’t know if anyone remembers this, but there was a lot of consolidation in the 3-axle space around 2008. Companies like Makerbot, Dremel, and others are sitting on a ton of 3D printing IP. The market had to slow to justify their investments, it didn’t make sense to release a printer that was obsolete before anyone could buy it. At some point, that dam is going to burst. Too many innovative startups are floating around and there’s too many known ways to improve - speed, quality, durability, form factor, in-print QA, software, etc are potential differentiation points. My guess is we’re going to see quantum leaps in these areas over the next 5 years as the market becomes more competitive.

4) I can’t see a future where GW doesn’t introduce print-on-demand. You’re right, not everyone has the time or interest in a 3D printer. A service that does the printing for you, with officially licensed IP, with rich customization options and easy-to-use software, could generate a lot of revenue. Beyond the wow factor, the opportunities to expand the market are enormous.

In > 90% of US counties, you can operate 3D printing services in any space that’s zoned for commercial with no additional licensure or bonding. Existing retail spaces are in malls / urban buildings / storefronts are already wired for commercial electrical load, and they lease so they can move. This means they could put machines in storefronts without major facilities costs. From a tax standpoint, the benefits to the company would be enormous - no tariffs on imported goods, ability to book licensing revenue anywhere on Earth, UK tax incentives for repurposing the skilled production workforce to more specialized, higher-margin tasks.

While there would be costs to making this move, current leadership is pretty smart. There are state of the art, high-capacity German fabricators capable of reliably pumping out several finished armies in less than an hour with low materials and maintenance costs. They’re big and expensive, probably not the right fit - but smaller and cheaper units are catching up. It’s probably not the right time today, but there’s going to be good reasons for GW to consider this within 5 years.

techsoldaten